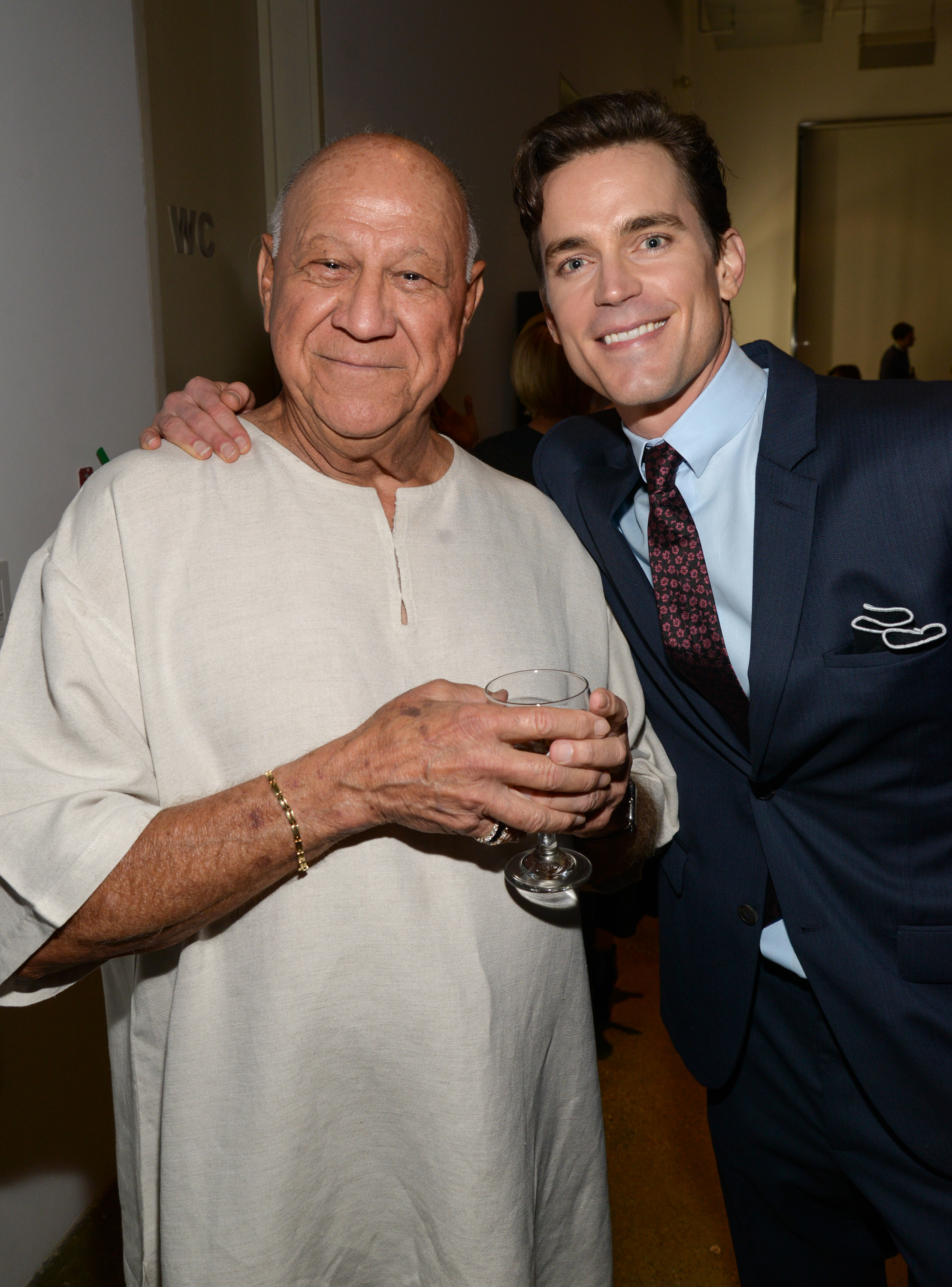

Performed by Matt Bomer

Each decade has brought major changes in the lives of LGBT people, and one man who’s seen it all is George Ciacci. Together with writer Callie Kloves, he shares the moving and unforgettable story of how he found love and learned about the ups and downs of life with one man who made all the difference. Watch the video performed by Matt Bomer, or read the full story below.

Every culture has a word for it. Every language. Every country. Here in the States we have quite a few. Gay. Queer. Fag. Where I’m from, it’s Mahu. It’s what they called me growing up on Oahu, Hawaii. Some used it lovingly. Others not so lovingly.

I was born to an Irish-Hawaiian mother and Italian father on June 10th, 1934, which makes me a Gemini. We’re bitches, but good ones. I’m the third of three boys and one of two gay sons. I always knew I was gay, and so did my family. My parents always supported me. No one seemed to care much. I was lucky that way. My older brothers always defended me to their friends. Those kids never wanted to fuck with me anyway. I was big and strong. They knew I’d knock them on their ass. I was good looking. Athletic. I went to the Olympic trials for swimming. The girls liked that. Oh, I’d been with women in high school. They were interested and, honey, I was still a teenage boy after all.

After high school I moved to Los Angeles. I started working in the gay bars on Hollywood Blvd. Being a bartender I knew everyone. I knew the scene. It was quieter then. Not like it is now. Not as out there. People were more low key. You could come into one of these bars, sit down, and not know where you were. But after you sat a while, well, it became pretty clear.

I moved through a few of the bars. There was Mickey’s. The owner was an old drunk. His sons ran the bar, both gay. They spent all their time fighting over who was more elegant. The father would be so out of it by the end of the night he’d put the money in the refrigerator and the rolls of quarters in the oven instead of the safe.

There were a lot of characters on the scene in those days. There were the ones with wives and children. There were the ones who found religion. And by religion I mean a spot in the bishop’s bed. I never judged. Everyone had their kinky moments. The actors who came into the bar you never mentioned by name. There was the travel agent who used his job to take his tricks all over the world. That was my world. And I saw it all happen from behind the bar.

The gay bars were dangerous in those days. There were raids. The cops during that era were really nasty bastards. They were all in cahoots. Fuckers. The vice squad would come to the bar. Plainclothes cops. They were beautiful, handsome men. They would go into the john, drop their pants and see who would take the bait. And if you did, they’d haul your ass off to jail. We all used the same lawyer, the one with the big hats and the glass eye. Slip him some cash in a brown paper envelope and he’d bail you out of jail or get you out of a DUI. He always told us to plead guilty. It was simpler, safer that way. No point in fighting it. It’s like killing a cockroach, he’d say. You kill one, a bunch more come.

I’ve been through a lot of shit. I’ve seen it all. But that’s life. And then there was Ben.

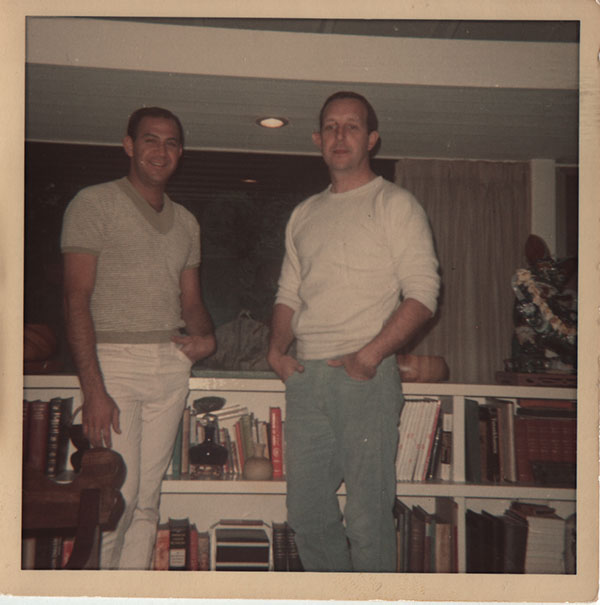

I was the bartender at the House of Ivy on Hollywood Boulevard. He walked in one night and sat at the bar. The night turned to morning. We were getting ready to close up. He was still there. He looked at me and asked, “Can I take you to breakfast?”

He was very handsome. There was no denying it. I wanted to. But I knew I had to make him wait. If he really liked me, he’d wait. So I said, “I’m tired. I’m going home. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

It’s not that I played hard to get. It’s that I wanted to see if he would come back. And he did. The next night. And the night after that. And every single night for a month. We finally got together.

He was from New York, the child of Polish immigrants, he was raised Catholic, conservative. They never knew he was gay, his parents. I never met them. We’d fly to New York, and he’d see his family. I’d stay at a hotel, or I would fly on to somewhere else, Europe maybe, and Ben would meet me later.

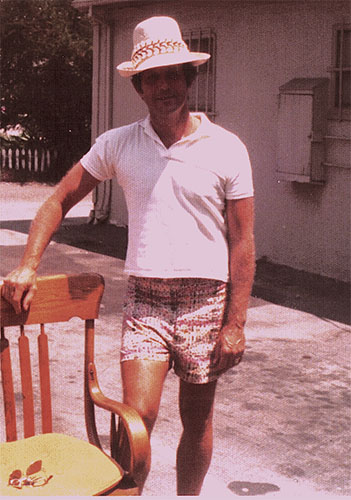

We traveled. To Europe and Bali and Australia. I’ve been all over this world. I’ve seen it. I’ve seen the discrimination. Every place I went to I would adjust. You had to. It was the smart thing to do.

Ben was educated, went to college. When I met him, he was a stock broker. He came to Los Angeles and worked his way into Hollywood. He started from the bottom, first as a grip and eventually settling in hair and makeup. He did makeup for Barbra Streisand and John Wayne. He was never the big gun, never the guy in charge. His boss got the credit but he got the hours, and that’s all that mattered. He didn’t care. Ben didn’t want to stand in the limelight.

I’m going to be honest with you: I couldn’t give a fuck about Hollywood. I was never interested in the industry and what was going on in it. I had seen it all in the bar anyway. I had a lot of friends who were going with people in the industry. They’d come into the bar or cruise Fountain Avenue. Let me tell you something, honey. This whole industry from make up to scenic, faggots in every department. But in the old days they were all so closeted. They were so afraid to let someone know they were gay in the industry. They didn’t want to be associated with homosexuals.

Ben was no different. He stayed in the closet at work. He would come home and tell me about some party he was invited to, some event at the Academy. He’d ask me if I wanted to go. I’d tell him, no. I can’t be bothered. But the truth was I wasn’t going to be the bitch in the closet. I wasn’t going to sit at that table and pretend I was his friend. He didn’t want to be seen with anyone who was loud and well I was loud. I didn’t give a shit. If someone says something to me I don’t like, I’m going to be polite and nice and tell them to go fuck themselves. I mean I’d do it in a dignified way but I’d still tell them to fuck themselves. That’s just me.

Later came AIDS. I knew a lot of sisters who caught it. My own brother was one of them. I’d go see him at Cedars. They had a whole floor for them. It was early then.

They still didn’t know what it was. They were treating him with chemo and radiation. He was just skin and bones, barely there. One day he soiled himself. That’s pretty common with this disease. The nurse didn’t come clean him for an hour. He rang the bell fifty times before they came to help. The world had changed so much but a lot of the attitudes hadn’t. My brother died not long after. We lost a lot of people during that time. But I still had Ben. I always had Ben.

It was me and him for over fifty years. We moved into the little house on Fountain Avenue and stayed there for forty years. We had a car. Ben always drove. I was a terrible driver. I was always crashing. It was better to let Ben take the wheel. It was a good life. Sure we argued, just like any couple. But I learned that whatever the argument, you have to turn the page. Forget and forgive and go on living. You just love one another.

Then Ben got sick. Leukemia. For the last four years of his life. We sold the car. He was just too sick to drive. There was no use for it. Eventually he had to leave the little house on Fountain Avenue and move into the hospital. I stayed there every night in his room. He told the doctors I was his half brother. He was still afraid of what they’d think of him. Even though the world was different it was hard for him to forget all those years before.

One day he said to me, “George, you have to marry me because you won’t get any of this.” I looked at him and said, “You fucker. You should’ve thought of this a long time ago.”

I think that’s the first time it hit me. The first time I thought, what am I going to do? Ben had always taken care of everything. He was the business mind in the relationship. I didn’t even know how to write a check.

We married, and a month later, Ben died. That was a hard time. I had lost the person I had spent over half my life with.

Ben’s pension stopped. Then his union benefits. They said they couldn’t recognize our marriage. We were married a month. They only recognized marriages after two years. At that point, Gay marriage hadn’t even been legal in California for two years. Our fifty years together didn’t matter if we didn’t have a piece of paper to prove it.

I think about now what we could have done differently. Why we didn’t register for a domestic partnership. Maybe it was because I was ignorant. Maybe it was because he was in denial. Maybe we both were. Maybe it was because we never thought marriage was possible for people like us. Our whole lives we were discriminated against for being unconventional. Now we were facing discrimination for not choosing the most conventional thing there is. Marriage. Go figure.

But maybe when you’re building a life with someone. When you’re falling in love. You’re not thinking about everything being taken away. About what would happen when he’s gone. I never thought that after five decades with someone, I’d have to prove the legitimacy of our relationship.

But maybe when you’re building a life with someone. When you’re falling in love. You’re not thinking about everything being taken away. About what would happen when he’s gone. I never thought that after five decades with someone, I’d have to prove the legitimacy of our relationship.

I keep Ben’s ashes in a small box. The box is decorated with shells. It’s a little nod to my Hawaiian roots. The box sits in the living room we shared for over forty years.

We talk everyday. If he gets nasty, I tell him to be careful or I’ll flush him down the toilet. That usually quiets him down. I’ll keep them here until I’m gone. Then we can be buried together. Just us two Mahus. For another fifty years and beyond.

George’s husband, Ben, worked in the industry for most of his adult life. He was a member of multiple unions, and he was receiving a pension before his death. Those union benefits were sustaining his life with George. But after Ben’s death, George stopped receiving those benefits. George thought he was out of options until a friend told him to contact the MPTF. And even though the unions do not, the MPTF does recognize George and Ben’s marriage… their 50 years of love and commitment.

George now receives the financial help he needs to buy groceries and pay his rent. George has also been assigned a social worker named Nina. She is George’s advocate and helps him communicate his needs to MPTF, but more importantly, she provides him with emotional support. Sometimes it’s just by talking to him on the phone. Other times she’ll drop in for a visit. They’ll walk to the local Farmers Market or just sit in his living room and talk… about Ben, about the neighborhood, and how it’s changed. As George would tell you, he doesn’t take more than he needs. And he doesn’t need much, just enough to get by, enough to not worry.